The Post Office lessons for ed tech

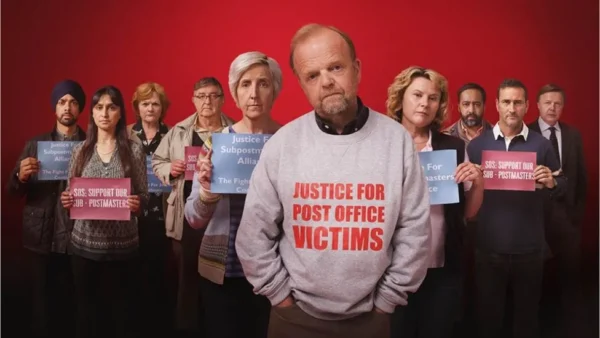

I expect we’ll see a lot of these types of posts so I apologise in advance for bandwagon jumping. For those outside the UK, there has been a recent TV drama, Mr Bates vs The Post Office, which has dramatised the Post Office scandal, where hundreds of sub postmasters were falsely accused (and convicted) of fraud because of a faulty accounting system that was rolled out in the 00s. The TV series has caused fresh outcry, actions and recriminations, and is probably one of the most important drams made in the last decade or so.

Like many people I had vaguely followed the story, but not until the TV series had I fully appreciated the scale of it, the impact on those involved and the duplicity of the Post Office senior management. People who are more knowledgeable than I can write insightful pieces about management cultures, or large IT system procurement. But one thing that I do know about is the kind of technology culture war that was in part responsible for the continued stance of the Post Office to victimise and blame sub postmasters rather than their technology. I say in part, because political ambition, career self interest, class attitudes and arrogance were probably all more significant factors.

In the intro of 25 Years of Ed Tech I set out the “adapt or die” narrative that is often levelled at higher education, with regards to educational technology:

An opinion often proffered amongst educational technology (ed tech) professionals is that theirs is a fast-changing field. This statement is sometimes used as a motivation (or veiled threat) to senior managers to embrace ed tech because if they miss out now, it’ll be too late to catch up later, or more drastically, they will face extinction. For example, Rigg (2014) asked “can universities survive the digital age?” in an article that argues universities are too slow to be relevant to young people who are embedded in their fast-moving, digital age. Such accounts both underestimate the degree to which universities have changed and are capable of change while also overestimating the digital natives-type account that all students want a university to be the equivalent of Instagram. Fullick (2014) highlighted that this imperative to adopt all change unquestioningly, and adopt it now, has a distinctly Darwinian undertone: “Resistance to change is presented as resistance to what is natural and inevitable” (para. 3).

I see some of this in the Post Office scandal. It was brought about by the introduction of a national accounting system using electronic point of sales, replacing the existing paper based system. They were not wrong in seeing this general direction of travel – think of where we are now. But I suspect they went for an over-complicated system when the technology was not quite ready. This sets up a binary narrative however – the old paper system in the 21st century or our new digital one. No other choice is available. Senior management were inevitably on the side of progress and change, while they no doubt viewed sub postmasters as resistant and old-fashioned.

This narrative becomes deeply embedded to the point of being meshed with identity. This explains (partly, although see those other factors above) why it was so difficult for those in charge to shake themselves from the pro-Horizon stance. It was in part, an existential crisis. They couldn’t be wrong that change had to happen could they?

Of course, the answer is that change probably did need to happen, but there were degrees and ways of that. It wasn’t a case of this change or no change, but that’s how these things come to be perceived. Which brings us to ed tech. We see a similar narrative often in play in our sector. Think MOOCs, and avalanches that were coming. Ed tech companies and thought leaders are the pro-change gang and fusty old academics, are, like sub postmasters, seen as out of touch.

And now, of course, think AI. Many prophecies of doom. Of “get on board or die”. And equally they other way dismissive cries of “it’s all rubbish”. What the Post Office scandal tells us is that these binary narratives are positively dangerous.

It also illustrates what happens when trust breaks down – did the Post Office really believe hundreds of previously loyal sub postmasters decided to become embezzlers overnight? It was easier to trust the technology than question that. We might do well to consider that when it comes to student plagiarism and proctoring also.

2 Comments

Doug Clow

Yeah, it’s easy to see the parallels here. Large scale digital transformation is hard, sometimes necessary, and will inevitably have problems. The key thing is how you do it – if you try to empower your staff you’ll do a lot better than if you try to empower bosses to micromanage. Up to that point there are clear parallels between the Post Office/Horizon/Fujitsu debacle.

Large digital projects always have problems. The good ones fix those early by listening and acting on feedback. Many don’t do that effectively: projects that have substantial failures are common. What’s not common is people being criminally prosecuted on the basis of obviously-buggy digital systems, and doubling down on that at every opportunity (even now!) to try to cover it up.

To me that’s what lifts the Post Office/Horizon/Fujitsu debacle into a huge, scandalous injustice on a very different scale to, say, a botched Canvas rollout.

mweller

Hi Doug! Yes, that doubling down is the truly shocking part, and as you say very different from anything we’ve quite experienced in ed tech. But I think in part it happened because of the rooting of identity that became associated with the technology. So a cautionary tale at least